There are no other places on this planet

Which have raised me as much

Attraction and disgust at the same time.

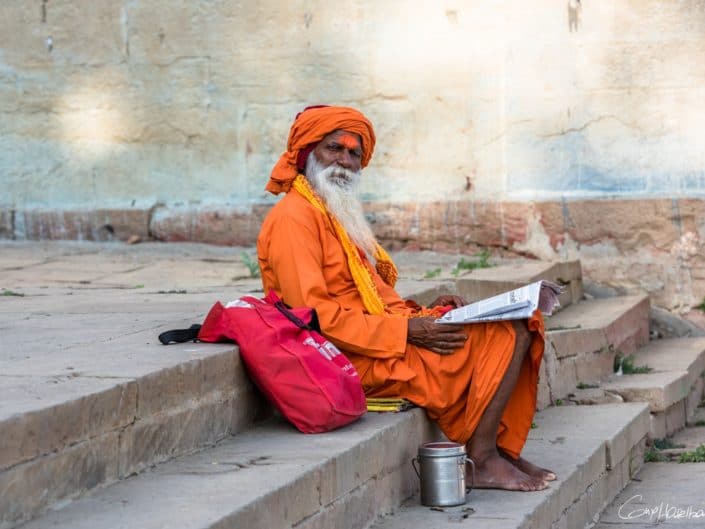

Un sādhu.

Varanasi stinks death and trembles with life.

It is an extra place and too much on a trip. Where everything is too much to give nausea.

Too much of everything that grows: It’s a cloaca. To choose and weigh this word, to be sure to use it wisely and to be sure that it corresponds exactly to the feeling, took me five days.

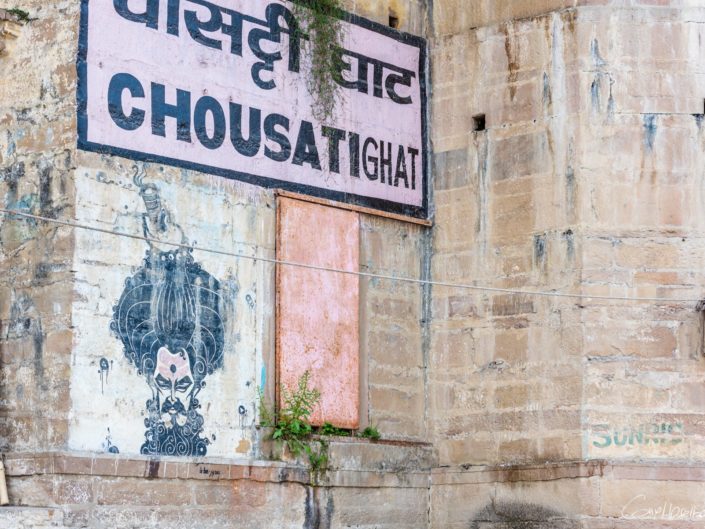

Les ghats de Varanasi.

Yes, Varanasi (Benares) and the Ganges are cloacals in every sense of this term. A repulsive, execrable city, a nightmare of incredible aesthetics. Not that of salons but that of the most abject gutters. Even the rats seem to have deserted these places for the campaign. The aesthetics of human despair. That of the most extreme misery, that of the unbearable, that of the incomprehensible, that of the improbable.

Like the city, the Ganges is a sacred weir. Ashes and human and animal carcasses are dumped while others,

just next to it, collect sacred water in small cans, drink it, wash, wash the clothes of others for a few rupees, bathe or Bathed their sacred cows.

Yes, I turned my head dozens of times, pinched my nostrils, held my breath, although equipped with a mask, not to breathe this explosive cocktail of unhealthiness, microbes, Odors like that of urine that everyone pours everywhere unrestrained, closed their eyes sometimes to avoid seeing the unbearable or to bear the irritation of extreme pollution. Yes, Varanasi is the moment of supreme truth in which one sees oneself as in a mirror through the decay of others, sickness, extreme poverty, old age, death and cremation.

Sur les ghats de Varanasi, au bord du Ganges.

It is the permanent spectacle of what one does not want to see, of what rejects. It is a jostling in itself, an endless questioning without end and without answer.

It is the remains of human carcasses that are broken with wooden sticks on the pyres to accelerate the combustion, pass to the next corpse and save wood, while the cows walk on the ashes still hot to nibble the remains of Funeral wreaths and flowers.

We finally leave the hell of a traffic of vehicles and rickshaws, so saturated that nothing advances, to walk then towards the Ghats and to find a little calm away from the noise of the tutk of the tuktuks. On the footpath, one passes through a dense and mixed crowd. Those who live on the sidewalk or even huddled in the gutter, those sacred vows which they allow themselves to go everywhere to defecate, in the narrowest alleyways to the middle of the crossroads where they end up lying.

Pèlerin au bord du Ganges.

Some will say that it is India in all its splendor. That India is unique and incomprehensible and that this is what makes it attractive. Of course.

For me the best memories of Varanasi are the providential moments of some pictures, but it is also the moment when I left the city, one day rather to be sure not to miss my plane for the weekly flight to Yangon from Gaya.

The third and last stay in Varanasi.

![]()

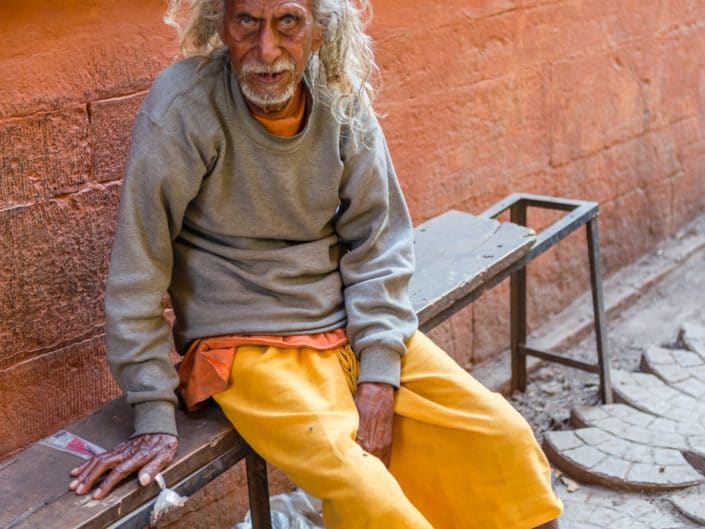

Le pèlerin handicapé au bord du Ganges.

I observed him at a distance for more than fifteen minutes, approaching his crutches painfully from the edge of the river. Then he crouched as close as possible to the edge, he laid his crutches and began to pass a little water on his sick legs. Then he pulled out a small mirror and put a white paste on the handles and face. The aesthetics of misery and human despair.

Le pèlerin handicapé du Ganges.

Sadhù.

Sâdhu “fake” uniquement là pour la photo.

Sâdhu “fake”.

Portraits of Varanasi.

La fille rouge.

Life on the ghats.

This ritual. Difficult to miss it if you go along the Ghats. He has many piles of wood, a thick smoke that has blackened the walls of buildings next door, and especially a pungent odor of burnt human pulpit. Around the pyre the cremation professionals are busy maintaining the pyre and charring bodies and regularly straightening the pieces of wood or parts of the body emaciated.

Around these places of cremations he has a crowd of people: The families of the deceased, the curious, the tourists, the bearers of wood and those who direct the cremations.

But some are trying to do a parallel trade by offering tourists permission for families to take pictures for a few hundred rupees. Curious.

Initially approaching this place I was warned several times shortly before the place “no photos here … to respect the mourning of families …” then once on the site others come to meet me To offer me permission to photograph. Faced with this incoherence and the lack of photographic interest, I preferred to store my camera and look with my own eyes.

Go to top

Leave a reply